“I was meant to have mental health inpatient care but I could not be admitted because [the hospital] could not provide the physical care I needed. I needed hoisted and that was a problem, so I could not go.”

GDA member.

From the outset of the first lockdown in March 2020, GDA began a ‘wellbeing’ ‘check-in’ service for members to find out how disabled people and their families were being affected and what GDA could do to support them.

The findings from GDA wellbeing check-in calls and survey not only highlighted the need for a service specifically to support disabled people’s physical, emotional and psychological wellbeing, but the failure in statutory services to provide this.

This report builds on this evidence, looking at the effects of Covid-19 and beyond, demonstrating that disabled people are aware of what is needed to support their wellbeing and how they can maintain or improve their mental health. However, it also demonstrates that there is a distinct lack of support from statutory services when a disabled person requires interventions for mental ill health.

Key Findings from Report

- 100% of participants said they do not/ did not feel heard or taken seriously when trying to access mental health services or supports.

- 85% of participants expressed concern around human rights not being upheld or eradication of rights, or legislation that may diminish their rights as disabled people.

- 45% expressed fearfulness of statutory mental health services and the resulting stigma from accessing services.

- 55% of participants expressed having suicidal feelings in the past two years.

- 100% of young disabled people knew what contributed to mental wellbeing and what actions they could take to alleviate low mood.

- 46% of young disabled people were getting the mental health support they actually needed (out with GDA supports).

Recurring Themes

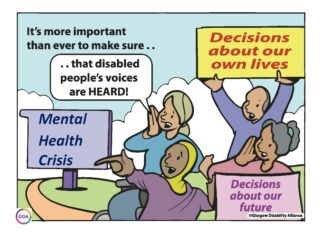

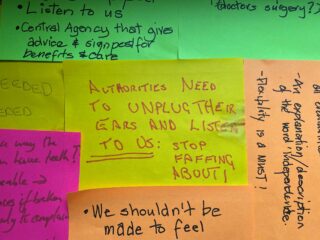

Disabled people were not heard. They were not taken seriously and often felt dismissed.

Disabled people found themselves having to rely on GDA and other community or third sector services when others halted at the outset of the pandemic, including at mental health crisis points.

There was a lack of trust in, and fearfulness of, statutory mental health services which have shifted from being there to support and “take care of” people, to a new position which is felt to be about detachment and disbelief.

Crisis intervention appeared to be offered after disabled people had taken actions to end their life, and not before. This was a cause of frustration to many participants who wanted appropriate preventative and timely support when their mental health was poor but before crisis point was reached.

It is noted with concern that many of the problems faced by disabled people stem from inequality, disadvantage, poverty and exclusion. Continual “micro-aggressions” such as not being believed, being dismissed and being discriminated against because of disability, being LGBT and/or being black, Asian or minority ethnic, also resulted in negative mental health amongst respondents including depression, anxiety and negative view of the world.

Funded by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Mental Health Anti-Stigma small bids fund and matched by funding from a variety of sources to widen the breadth and depth of the research, the research explored three main themes:

1. General Mental Health Anti-stigma and Discrimination Work

2. Reducing Stigma and Discrimination around suicide issues

3. Reducing Stigma and Discrimination related to Children and Young People’s mental health.

Research was undertaken with our Young Disabled People’s Group, LGBTQIA+ Disabled People’s Group, Black Minority Ethnic Disabled People’s Group as well as disabled people taking part in our learning & support programmes programme.

Many of the disabled people who took part in the research, described living situations that were not conducive to good mental health and wellbeing.

Poverty, poor housing and lack of care and support were amongst many challenges sited. People described being unable to access washing and cooking facilities or outdoor space and feeling unsafe due to antisocial behaviour, including from immediate neighbours. GDA staff recounted examples of many people they are supporting whose home situations are leaving them at tremendous physical and psychological danger. This included people where lack of social care support resulted in them living in dirty, cluttered homes, with no access to support to resolve these situations, causing a downward spiral into crisis.

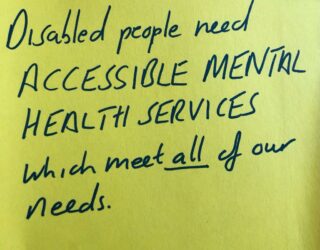

Disabled people who experience mental health crises reported struggling to find services which recognised both their mental health and physical needs in relation to disability,

“I can’t just ‘get more exercise and fresh air’. I don’t have the support I need to get out and do that. It’s frustrating that the system can’t see you and recognise your whole life, and how this affects you.”

Changes are required and diverse disabled people want to be involved in the development of services that meet their specific needs, including mental distress, suicide prevention and bereavement services. We must work together to enable this to become a reality.

Recommendations

- Involve and listen to disabled people

- Eliminate barriers to access

- Invest in accessible and holistic Wellbeing Services

- Address Gaps in Services

- Promote and Uphold Human Rights

These recommendations chime with those made by the Social Renewal Advisory Board for Scotland which outlined a specific call to action to realise the human rights of disabled people.

“It seems that most barriers we face could be solved by people listening to us – sometimes we only need simple changes which could make a big difference.”

GDA member.

GDA’s Wellbeing service remains a key priority for GDA in 2022 and beyond to meet the “supercharged” inequalities and need identified.

“I could not get in touch with my CPN – they seemed to disappear and no-one would help me, even though they knew I had a suicide plan. GDA Wellbeing saved my life, quite literally. There’s no doubt I would not be here if I hadn’t called them.”

GDA member.

Read our report: “Disabled People’s Mental Health Matters” at this link: https://gda.scot/resources/disabled-peoples-mental-health-matters/

Related Articles

The real cost of living for disabled people

Challenge Poverty Week took place last week from 3 – 9 October, highlighting the injustice of poverty in Scotland and the need for collective action…

Read More

Young disabled people take action on climate change ahead of COP26

“I have really enjoyed the whole legislative theatre process and having my concerns as a young disabled person highlighted and my voice heard by to…

Read More

#ClimateFringeWeek

With #COP26 on the horizon, Glasgow is preparing and poised to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate…

Read More